If you keep up with any publications that review or generally discuss headphones, you’ve probably seen the phrase “Harman curve” thrown around a fair bit. I mention it often in my own reviews.

So what is it exactly? And why is it purportedly so important? That’s what I’m going to discuss in this article, as well as offer my personal opinions on the topic.

The Harman curve isn’t something that’s physically literal, as if to discuss the comfort of a headphone band atop one’s head. Rather, it is a two dimensional plot graph of volume vs pitch.

The word “curve” is often used to describe any such functional relationship in math, which might not necessarily look like a perfect curve per say, but might actually look like a straight line, or in the case of headphone measurements an irregular squiggle.

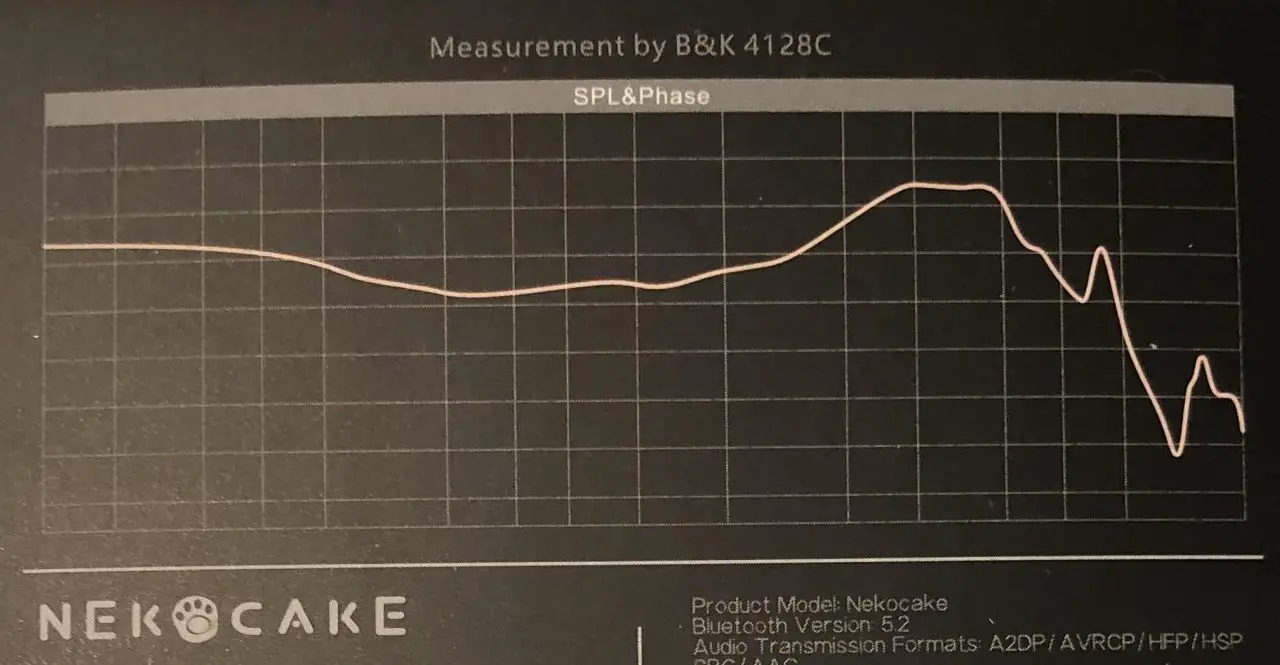

The above graph is what’s called a frequency response curve, which is the measured output/volume of sound (in decibels) across the range of pitch from low to high (in hertz).

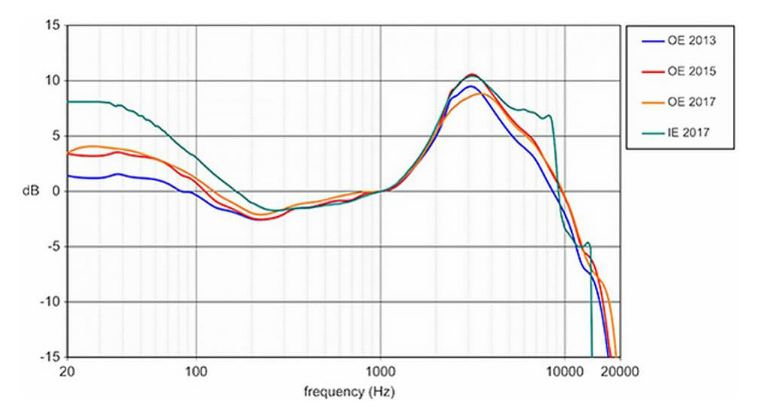

The Harman curve, alternatively, isn’t really a measurement so much as it is a theoretical target that’s based upon research of people’s listening preferences:

The idea behind it is that a company that’s manufacturing a pair of headphones wants to get their frequency response as close to the Harman curve as possible for them to sound the best, at least by Harman’s standards.

And this begets an obvious question: Does the Harman curve actually “sound” the best? and what does “best sounding” actually mean in general? More on that later, but first lets talk about how the Harman curve came to be and why it is in fact such a popularized standard.

How The Harman Curve Was Created

The eponymous Harman curve was developed by Harman International, a leading audio equipment manufacturer, and a team of their scientists and audio engineers led by a man named Sean Olive, who is a major figurehead in the audiophile community. Their goal was to answer the ostensibly simple question: what should headphones sound like? Or in other words: what style of headphone tuning is most pleasing or preferred by the average person?

What ensued was extensive research and experimentation, and it has also been ongoing. Fully expounding the details of it all will get us a little lost in the weeds, but a very basic summary is that Olive’s group had a bunch of people do blind a/b testing of different tracks and then choose which they preferred. From that, they slowly narrowed down preferences for enough frequencies to construct a response curve graph.

(If you are interested in the full details this Reddit thread has a good explanation and subsequent discussion.)

The Harman curve is essentially their answer to the question: a representation of and target for the ideal sound signature for headphones, based on what people actually said they preferred with a lot of testing.

What Is the Target Frequency Response of an Ideal Pair of Headphones According to the Harman Curve?

The shape of the Harman curve is colloquially called a “U” curve in the world of headphones – where the bass and treble are tuned up by an audibly noticeable difference, with a natural valley across the mid range that bottoms out at around 200 Hz, which is around the middle of a cello’s range for reference. The peak is around 3k – 4k Hz, which is right around where things like high hats, cymbals, and vocalized consonants are.

Why Does The Harman Curve Sound Better Than a Flat Frequency Response Curve?

A neutral and perfectly flat frequency response curve would theoretically reproduce the sound of a recording as it was, without any bias, and it stands to reason and might even seem intuitively obvious that it would sound the best. After all, if the sounds of the instruments, vocals, etc. that come out of your headphones are *exactly* like the actual sounds that came out of those recorded instruments, singers, ect., then you’re essentially hearing the “real” thing.

So why, then, do people, according to Harman’s research, prefer a biased frequency response with tuning that kind of looks like a shallow “U”?

There are a lot of proposed reasons, some of which are more theoretical and harder to empirically prove than others, but to name a few:

- the way that room and spatial acoustics affects sound, which headphones effectively have to replicate

- performance limitations of headphone drivers, particularly single dynamic drivers, which are what’s usually used in budget earbuds

- subjective human bias in sound perception

- human ears sometimes have more or less trouble hearing various frequencies

- modern popular song writing, recording, and mixing practices

- sound that holds up better in the face of external noise

The thing is, why it’s true doesn’t really matter ultimately. If the research shows people overwhelmingly prefer certain emphasized frequencies, then that’s what headphone manufacturers probably should and almost always do try to target.

My Thoughts: A Reviewer’s Perspective on the Harman Curve

To date I’ve published around 100 headphone reviews on this site, and have listened to yet many more. And if someone were to ask me: do I think the Harman curve sounds better than a flat/neutral curve? My answer is definitely yes, most of the time, and especially so with budget earbuds – the best sounding ones almost always utilize Harman style tuning.

I find, perhaps ironically, that Harman curve tuning actually sounds more “real” than neutral tuning. In my experience, when you reverse Harman style tuning with EQ, the sound is thinner, narrower, and introduces the unmistakable hollow, honky, boxy/cupping sensation.

The Harman curve style tuning, in contrast, sounds wider and more immersive, fuller with a nice airy sensation, and more detailed, especially with the quicker sounds like cymbal and snare taps, fast upper guitar solos, and vocalized consonants like “s”, “t”, and “k” – the kinds of micro sounds that make each instrument, singer, etc. feel very discrete, clear, and crisp.

In my experience doing headphone reviews, if there’s a general issue with the tuning and sound signature just sounding kind of off, and there’s a possible fix with an EQ app, it’s almost always raising those bass and highs by about 3 or more dB, just like the Harman target curve says sounds better.

And so in conclusion: good science and research is great because it helps us understand more and more what’s actually true or not.